After releasing several succinct investment cases, this new series will delve deeper into each business to provide greater clarity into what makes them truly unique. We begin with Richemont, a fine jewellery and watches powerhouse and true hidden gem in luxury. Its brands are timeless having endured centuries of wars, revolutions and recessions. The below provides a snapshot into some of its leading brands.

Since the core earnings driver and the bulk of earnings (95%) comes from its Jewellery segment (primarily Cartier and Van Cleef), the focus of the discussion will be on why these brands can deliver durable growth over the long-term. The below shows the group earnings split and how it has changed over time.

Company History

The history at Richemont has been far from conventional. The origins actually started in tobacco under Anton Rupert in 1948, who recognised the recurring and resilient nature of the business model. Initially known as the Rembrandt Group, the business grew from tobacco into wines, spirits, food, mining and banking and eventually becoming the fourth largest tobacco company globally.

It was not until the 1960s when the group entered luxury when Rupert acquired a 20% stake in Cartier Americas in exchange for a licence to produce Cartier branded cigarettes. Rembrandt made a few more luxury acquisitions before spinning off its international assets into a new group, Richemont in 1988. The company was listed on both the Swiss and Johannesburg stock exchanges and had the goal of becoming a luxury powerhouse. Richemont quickly established itself here with a number of notable acquisitions including; Vacheron Constantin (1996), Panerai (1997), Van Cleef & Arpels (1999), A. Lange & Söhne, IWC Schaffhausen and Jaeger-LeCoultre (2000). See below.

Cartier History

Cartier was founded in 1847 when Louis-François Cartier took over his master’s workshop. Cartier initially acted as wholesaler selling to other workshops, with the aspiration to shift to the wealthy consumer over time. The workshop survived multiple tumultuous periods - one being the Siege of Paris in 1870, where they bought cut priced jewels from desperate locals and sold them across the sea to the English.

Cartier’s global expansion began when Louis-François’ three grandsons Louis, Pierre, and Jacques took over. Each brother had a unique strength that enabled success, Louis for creative inspiration, Pierre for business acumen and Jacques for gemstone expertise. Cartier opened its first boutique in Paris in 1899, followed by more locations across the Americas and Europe.

The company has constantly been associated with royalty, celebrities and rich tycoons including King Edward VII, Indian Maharajahs, Belle Epoque princesses, Russia Grand Duchesses, and the Vanderbilts and Rockefellers.

Following Pierre’s death in 1964, the Cartier family decided to sell its branches across Paris, London and New York to a buyout offer led by Robert Hocq. Within this group of investors was Anton Rupert who as described above took a 20% stake in Cartier Americas. In 1979, Rupert acquired a majority stake and unified the three companies into Cartier Monde and in 1993, Richemont consolidated this majority stake.

Van Cleef & Arpels History

Van Cleef & Arpels was born when the daughter of a gemstone dealer Estelle Arpels married the son of a stonecutter and diamond dealer Alfred Van Cleef. The combined love of gemstones and jewellery saw Alfred and Estelle’s brothers open the first Van Cleef boutique in Paris in 1906. The brand cultivated a unique style with exclusive jewellery for evening wear, attracting many businessmen and aristocrats.

In the early 1900’s Van Cleef produced numerous iconic designs inspired by different cultures across Japan, China, India and Egypt. Innovation was at its core using techniques to set gemstones without any visible prongs, which enabled gems to fit exactly into place on rails. This required expert craftsmanship and left little room for error. See below.

Much like Cartier, it was not until the three son’s of then CEO Julien Arpels took over that international expansion began with the group expanding into Japan, China and the US.

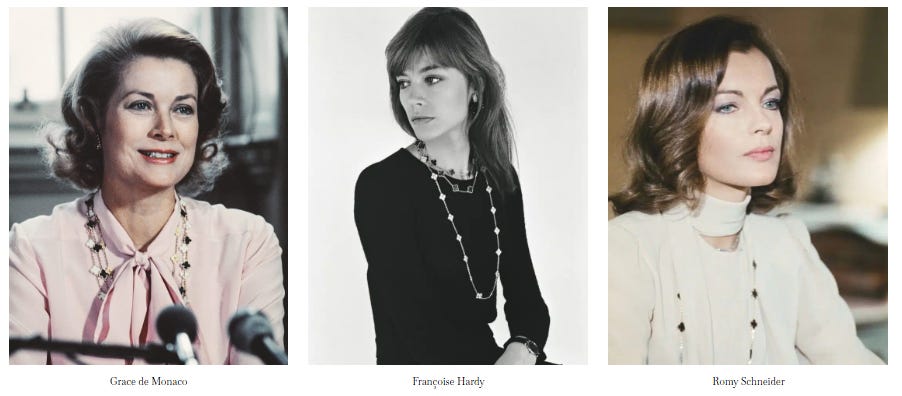

In 1968, the Alhambra long necklace was first released with the signature four-leaf clover becoming a symbol of good fortune. The collection was inspired by quatrefoil motifs found on the Moorish tiles of the Alhambra Palace in Granada. The collection has a strong association with luck and charm which is best described by Jacques Arpels, a nephew of one of the founding families “to be lucky, you have to believe in luck”.

Van Cleef has evolved its collections with different colours, forms and dimensions while keeping its enduring designs. The family decided to sell a 60% majority stake in 1999 to Richemont, with full ownership transferred in 2003.

Why are these brands special?

As explained above, the brands have a unique history. They are associated with heritage, exclusivity, and craftsmanship, all of which contribute to a enduring sense of timelessness. New entrants unfortunately cannot go back in time and replicate this success. Cartier and Van Cleef remain two of a handful of fine jewellery brands that have stood the test of time.

Brand equity has grown over 100+ years by increasing desirability and carefully managing supply with excess demand. For example, the Alhambra collection is regularly out of stock while Cartier’s items are unaffordable for most of the population. Investments in innovation, partnerships, marketing and distribution have further enhanced desirability. According to Interbrand, Cartier’s brand value has outperformed its closest peer Tiffany & Co since 2010.

The brand power is what makes these businesses special. Iconic designs developed over time are intellectual property (IP) that enhances these brands. For Cartier, designs have dated back 100+ years, a sign of the durability of jewellery icons which are less subject to fashion changes. These include:

Santos watch in 1904 made for Louis Cartier’s friend who found it inconvenient to constantly check his pocket watch

Tank watch as a tribute to the armoured vehicles during WWI

Love bracelet created in New York in 1969 to signify the eternity of love bonds

Juste un clou in 1971 to show beauty in everyday objects such as nuts and bolts

Panthère de Cartier in 1983 to resemble a panther and evoke its characteristics

For Van Cleef, the Alhambra (described above) and Perlee collections are the main icons. The Alhambra necklace can be seen below on various past celebrities.

The brand associations and stories around these designs are unique. In addition, production is difficult as the processes are often manual in nature and require years of training before artistic craftsman can make more complex designs. By way of example, the Alhambra motif uses a complex casting technique to melt the metal into a shape before gemstones are transferred on. With limited margin for error, expert maisons and the advantage of scaled production help achieve consistent high quality finishing.

While independent jewellers have sought to replicate designs, this is difficult to achieve at scale. Richemont has >€20b in revenue and significant purchasing power to attain volume discounts and can source supply effectively during tighter periods. Key talent also mainly resides in Europe, a cornered resource for the group.

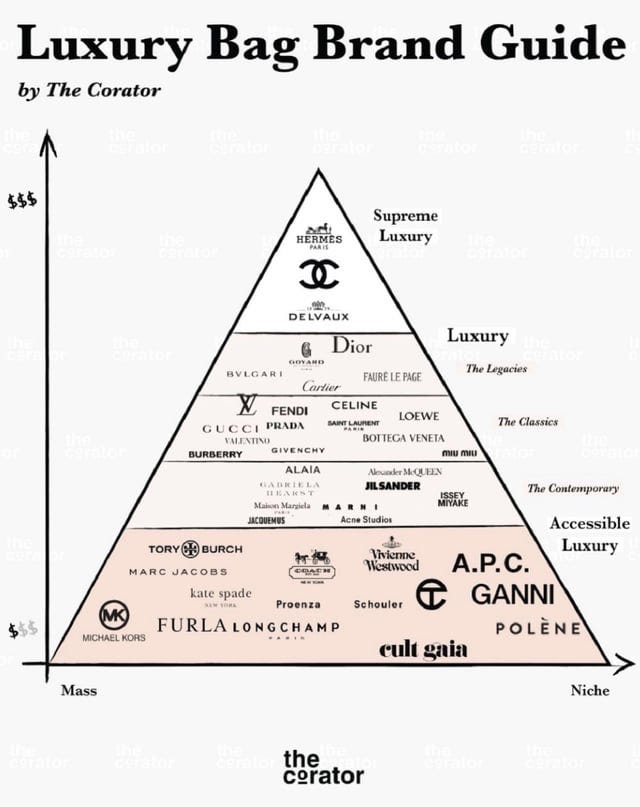

A combination of brand, IP and scale has seen high barriers to entry and strong pricing power. This is likely why the industry is quite consolidated with only a small group of leading luxury jewellery brands primarily based in Europe. These competitive advantages are durable and position Richemont to extend its moat and outright leadership. The focus now is to become similar to Hermes in leather bags and Rolex in watches. With former Hermes CEO Patrick Thomas on the board and a more focused strategy, they are heading in the right direction.

Competitive Environment

The fine jewellery market is highly consolidated, with the primary scaled players being Cartier, Van Cleef and LVMH owned Tiffany & Co. and Bulgari. Luxury brands such as Hermes, Chanel and Louis Vuitton have solid jewellery collections but it forms a smaller part of revenue. My internal estimates have the top 4 players operating with around 60% share.

This compares with leather bags where competitive intensity is higher with multiple brands operating at scale and with unique propositions.

Among the fine jewellery brands, Cartier and Van Cleef offer premium pieces with royal designs, quality craftsmanship and European heritage. Core materials include gold, gemstones and platinum. In comparison, the nearest competitor Tiffany uses a sterling silver base and has a wider range of product categories at lower price points. This exposes it to a greater portion of aspirational consumers.

An indicator of desirability and brand equity are second hand resale values. My analysis of second hand websites shows that Cartier tends to hold its value around 10% more in comparison to Tiffany. While Van Cleef due to low stock and high demand holds most of its value.

Although, Tiffany have performed well under new owners LVMH. New leadership has come in and reinvigorated the sales team and developed a higher performing culture. The strategy is solid as it seeks to replicate the success seen at Richemont by developing icons and refurbishing stores which have seen sales grow 25% upon reopening. Profits have doubled since the acquisition in 2020.

Overall, the fine jewellery market is highly attractive given the consolidated and rational competitor set. Although not immune to competitive threats, Richemont is well positioned with a differentiated, premium offering, high levels of desirability and a consistent strategy that prioritises long-term investments.

Are they gaining share?

Within the branded luxury jewellery market, Richemont has been gaining share. Since 2010, Jewellery Maisons have grown at a 13% CAGR, above industry growth rates. Share is estimated to be 35% as seen below.

The strong market position, stable industry dynamics, competitive differentiation (scale, brand and IP) and latent pricing power should enable them to continue growing faster than the market.

Why does the industry shift from unbranded to branded?

The jewellery market is experiencing an underlying shift from unbranded to branded. Share of branded has gone from 17% in 2019 to 27% in 2024 as seen below.

In comparison, other consumer good categories such as watches, shoes and leather goods have branded share at 80-100% levels. The consumer affinity for brands is strong, as depicted by the success at Ralph Lauren which has built an image around quality, craftsmanship and elegance in a commoditised space. The company has developed classic designs with founder Ralph Lipschitz noting “It’s not about newness or oldness, it’s about timelessness and the way you wear it that makes it better.”

There is no reason why fine jewellery can’t replicate this success, particularly among the larger players. People love to show off wealth and status, and just like watches, bags and clothing, branded fine jewellery can be another avenue to achieve this.

Furthermore as the leading fine jewellery brands build scale, it allows them to innovate and invest more into marketing and distribution. Cartier continues to cultivate a symbol of exclusivity around its red box and an image that owning a Cartier piece is not just a purchase but an investment in a legacy of artistry and refinement. Growing this awareness globally and especially across emerging countries is a further driver for the shift to branded.

If we invert this, independent jewellers who represent the unbranded portion should lose share. They do not have scale, marketing, trust and brand power. There is also a greater loss of value following purchase. More research and care needs to be taken when buying from independents. Rather, brands offer the peace of mind around quality craftsmanship and ethical sourcing.

For these reasons, it is likely the shift to branded continues to grow from the low base of 27% towards 50% levels and beyond. This drives industry growth rates of low-double digits.

Luxury Industry Growth Drivers

Historically, the personal luxury goods market has grown at mid-single digits annually. 2024 saw a general slowdown with spend broadly flat at €363b due to weaker China demand and lower spend from aspirational customers. Jewellery represents 9% of this, and has compounded faster at 9% since 2010.

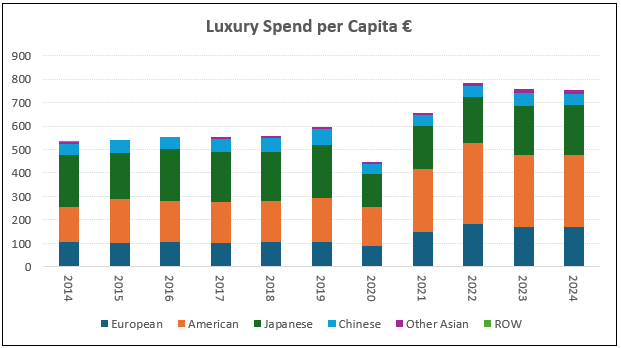

Since 2019, growth in personal luxury goods has come from a resurgence in demand from local Europeans and Americans with spend up 10% annually. Spend from the Chinese has fallen due to economic woes. The below shows luxury spend is dominated by ethnicities from developed markets.

While developed markets are important, the coming decades should see incremental growth coming from emerging regions such as China and Other Asia including India, South-East Asia and the Middle East. These regions have lower luxury spend per capita, a high propensity to spend and larger populations. As awareness and wealth grows more broadly here, this should expand the addressable pool of consumers desiring and being able to afford luxury.

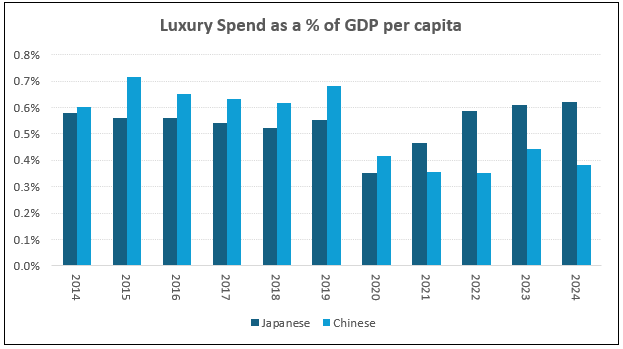

If we just focus on China, luxury spend as a percentage of GDP per capita (average annual earnings) is quite high and was previously the highest amongst all regions. This shows a willingness to buy luxury goods provided they have the capacity. Recently, we have seen spend reduce due to economic weakness spurred by a declining property sector. We expect this to be more cyclical than structural given the clear macro pressures (GDP and export pressure) faced across multiple arenas rather than consumer preferences changing.

Over time, spend should return as consumer confidence increases with the ability to re-bridge the gap with the more mature Japanese consumer over time. See below.

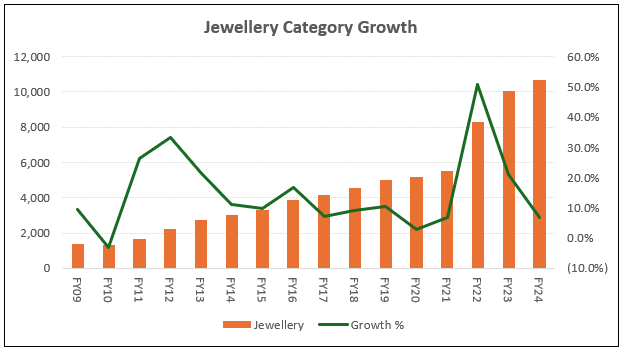

To put this all together, the personal luxury goods industry can grow at mid-single digits driven by growing wealth, an emerging middle class and pricing increases. Richemont’s Jewellery Maisons can grow faster than this given its exposure to the attractive jewellery market (double-digit growth) and watches (mid-single digit growth). The mix of jewellery to watches has also shifted from 50% in FY10 to 75% in FY24.

The mix shift and share gains has seen revenue compound at 13% per annum since 2010 driven by 16% growth in jewellery and a 7% growth in watches. My forecast estimates have more modest revenue growth at 9-10%, implying low-double digit jewellery and high-single digit watches growth. This seems reasonable considering the leading brand position, industry tailwind and inherent pricing power and implies only modest share gains.

Business model

We explore Richemont’s business model and explain why it is a highly attractive. Revenue is generated from selling jewellery and watches at a premium with prices ranging from a thousand to millions of dollars for some unique pieces. As explained the consumer is willing to pay for the quality, craftsmanship, heritage, service, enduring appeal, timelessness and beauty of the product.

Products are manufactured across Europe with the main materials being gold, platinum, steel, diamond and gemstones. Richemont has raised prices to offset cost headwinds from an appreciating gold price and Swiss Franc. This has enabled the group to maintain gross margins close to 70%, similar to other leading peers below. This compares with consumer discretionary brands who have gross margins of 30-50%.

To fulfil global demand, luxury goods players only need a few stores per city. Cartier already has a scaled global store network with growth coming from higher throughput per store. The below shows that the store networks at Cartier and Hermes have actually decreased over time, while sales have expanded. The model is capital light with the main expenditures being refurbishments or relocations. We note Van Cleef’s store network is around half the size of Cartier so there is further runway to grow there.

The operating costs to run a retail store are largely fixed around staff costs and lease commitments. Therefore, as sales per store grows over a largely fixed cost base, this should deliver inherent operating leverage. McKinsey explains this in its fine jewellery report “With a fixed cost base of roughly 60 percent of revenue, the profitability of players in the fine jewellery and watch industries is determined by scale, exposure to higher-margin direct-to-consumer channels and the pricing power of their brand.”

We have seen this phenomenon play out already at scaled peers Louis Vuitton and Hermes. Although they are primarily in fashion and leather goods, there is no fundamental difference as gross margins are comparable at 70% and the operating business model is similar. These players have sales per store at least 40% greater than Cartier, which has enabled them to generate operating leverage across selling, general and admin expenses. Given pricing power and leading brands, the Jewellery segment can maintain gross margins close to 70% with a clear runway to grow sales per store and operating margins closer to peers at 40%.

Richemont operates a relatively capital light business model with capex to sales of 5% and working capital to sales of 35%, which reflects the need to build up inventory. Capital is allocated relatively well with ROIC of 17%.

YOOX Net-a-Porter (YNAP) Divestment

Richemont began to look interesting when the decision was made to divest the troubled online luxury venture YNAP. The business had been plagued by growing losses and a weakening competitive position while being a clear distraction.

Richemont entered the online luxury space in 2002 acquiring an initial 30% minority stake in Net-a-Porter which was seen as a revolutionary and disruptive force selling luxury goods on the internet. Richemont increased its investment in 2010 taking full control and then in 2015 merged with YOOX Group to form YNAP, taking a 50% ownership stake of the combined business. In 2018, Richemont acquired full control of YNAP for a cash outlay of €2.4b. In hindsight this was a major capital allocation misstep as the business has struggled to grow financially and operationally under Richemont’s full ownership.

The core issues have stemmed from obsolete technology, an inventory heavy business model that was outcompeted by Farfetch’s capital light approach and conflicts of interest with competitors such as LVMH and Kering. In 2022, Richemont attempted to offload a majority stake in YNAP to Farfetch and Symphony Global, taking a write-down of €2.7b along the way. Chairman Rupert noted “Unfortunately, we took too long to migrate from a 1P or a linear model to a hybrid model, and this will give our Maisons the opportunity to have access to the best technology and best technical partners,”.

However, the deal collapsed after Farfetch was acquired by South Korean e-commerce company Coupang. It was not until mid-2024 that Richemont secured a new buyer: Mytheresa. Under the agreement, Mytheresa would acquire 100% control of YNAP. Financially, the deal raises some questions - Mytheresa will receive a cash position of €555m and hold no financial debt, while Richemont will receive a 33% stake in Mytheresa’s fully diluted share capital, with a market capitalisation of $700m. As a result, Richemont took an additional €1.3b write-down.

While not an ideal financial outcome, the divestment allows Richemont to offload a business that would have continued to deteriorate under its ownership. The move also enables Richemont to streamline operations and focus on its core business, while still being exposed to online luxury through its stake in Mytheresa. In preparation for the transaction, Mytheresa has rebranded its parent company as LuxExperience. The deal remains subject to regulatory approval and is expected to complete soon.

What is happening in Watches?

We haven’t really spoken about the Watchmaking segment. The company has leading brands including A. Lange & Sohne, JLC, IWC and Vacheron Constantin. See below.

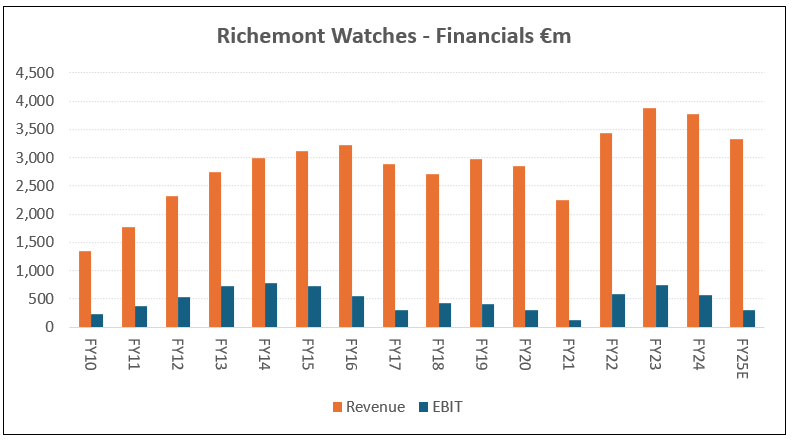

The segment has seen fluctuating revenue and margins.

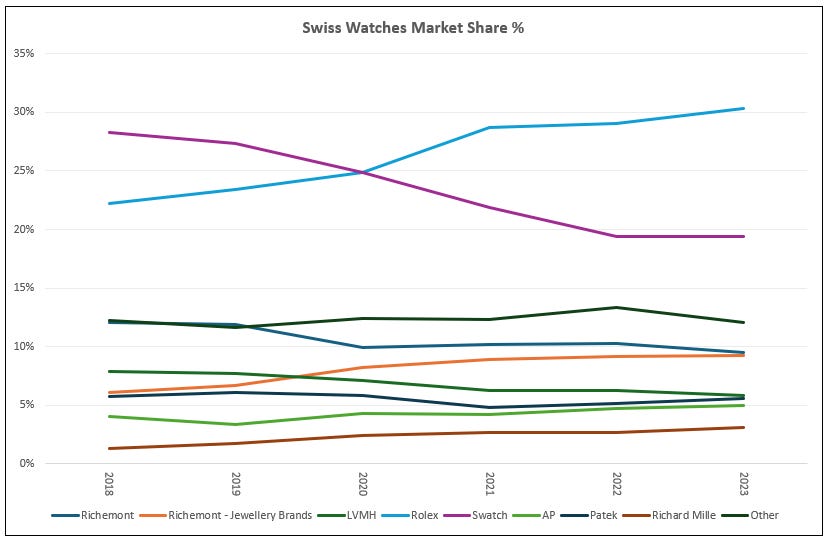

Richemont’s Watchmaking segment has lost share to leading players such as Rolex, Patek and AP due to it owning some lower quality brands and having greater exposure to China. Note, the watches business within Cartier and Van Cleef have gained share. The outright market leader is Rolex who has 30% market share and has mainly gained share from Swatch.

Share losses, an outsized China exposure along with a slowdown in the watch industry has seen sales and operating margins fall below 2017 lows, if we exclude COVID.

In 2017, the low margins came from the need to buy back stock mainly in the Asian grey market to reduce discounting and improve desirability. The business has since reduced its high Asia wholesale exposure and has shifted to a more direct retail model which requires a higher operating cost base. Margins have rebased structurally lower but it has now become a better business with greater control over stock to manage and navigate the current slowdown.

The longer term watch dynamics are favourable. US and China watch spend is low in comparison to more mature regions such as Japan. Watch spend as a percentage of GDP per capita in China and the US is 0.04%, half that of Japan and Europe at 0.08%. There are no structural reasons preventing this gap from reducing over time.

In addition, Rolex as the market leader is selling around 1m watches annually. This is not an insignificant amount and to ensure continued desirability the company will need to manage supply increases. There remains room for multiple winners. Richemont is well positioned with a range of high-quality brands. As sales recover over the medium-long term, margins can lift from current cyclical lows and increase to more appropriate levels. Similar to Jewellery, its really a scale game and about driving more sales per store. My forecasts do not have any meaningful upside in revenue or margins.

Financials

Richemont has delivered consistent growth over the cycle. The below shows the durable growth of the core Jewellery segment. Revenue has only declined once in the last 14 years.

The group is highly diversified across regions with lower exposure to China now.

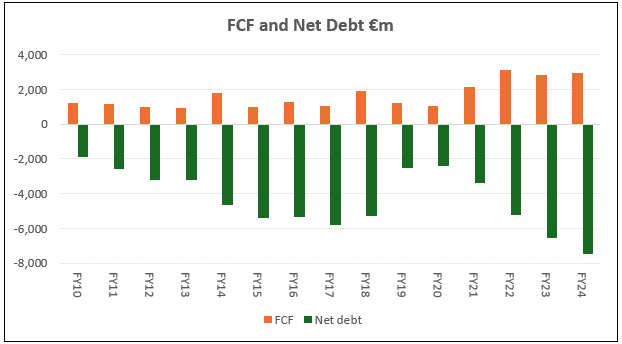

Richemont has consistently operated with net cash and generates solid cash flows.

The group can compound revenue at high single digits and earnings at low double digits. The payout ratio is around 50% and represents a 2% yield.

Management Team

Richemont is led by Chairman Johann Rupert who is conservative and has controlled and run it like a family business. The company has been net cash since 2010.

The recent management team reshuffle has seen Nicolas Bos (formerly CEO Van Cleef) take over as CEO from Rupert, while Louis Ferla is now CEO of Cartier and Catherine Renier CEO of Van Cleef - both internal hires from the watchmaking segment. These changes bring more autonomy to each respective business unit and is expected to bring greater innovation and decision making. Rather than most decisions being centralised through Rupert.

Importantly, management has been promoted from within ensuring continuity of the culture which strives for incremental improvements and maintaining the heritage of brands. The Richemont mission “is to craft the future by nurturing the distinctive craftsmanship, innovative spirit and creative inspiration of our people. In this way, we aim to create long term value for all our stakeholders.” The management team thinks long-term and understands the importance of brand desirability.

What happens in a recession?

In 2008, luxury spend decreased 1.2% and then 7.5% in 2009. If we were to face another recession, we could expect similar if not greater impacts, given the larger mix of aspirational consumers. Although luxury spend has shown resilience despite weakness in China and the aspirational consumer in 2024.

The jewellery sector is even more resilient given the higher Average Selling Prices (ASP) and greater levels of self-purchase. This leads to less promotional activity and lower cyclicality vs what is seen across lower end, commoditised sub-sectors. Richemont Jewellery sales fell 3% in FY10 and have since grown every year. Further, the mix of jewellery to watches has increased from 50% to 75% and adds further resilience.

Risks

If we think about the core Richemont brands, they have prospered through many world events. The primary risk to this continuity is how these brands are managed. The true luxury playbook involves careful management of supply with demand along with marketing and distribution to increase desirability over time. It is important that Richemont does not focus on strategies to drive short-term volumes or outcomes, as this can reduce the desirability of brands and ultimately lead to share losses. We have seen this occur at a few other brands ie Gucci. A careful strategy under Chairman Rupert is highly likely.

The other major risks are within the Watches and Other segments which are lower quality, have lower margins and are more cyclical. We could see revenue and margins fall further as the segments are more exposed to general industry dynamics. As explained earlier, Watchmaking has become a better business with more direct retail stores and control over end product demand. The segments also represent <5% of group earnings.

Lab grown diamonds have also been floated as a risk. Cartier has lower exposure here given its gold and platinum bases. Currently lab grown has a low association to exclusivity. If this changes, Richemont can shift its jewellery to include it.

Financial risks do exist, mainly around the ability to sustain industry leading revenue growth. The China risk has reduced with revenue now 20% of the business from 35% post COVID. Ongoing trade disputes between the US and global counterparts could see tariffs lift costs and prices, which would likely have a negative effect on volumes. Rises in Gold and Swiss Franc have also been headwinds in the past. These are all risks that can be managed over the medium to long-term given the company’s pricing power and diversified revenue exposure.

Richemont is net cash, run conservatively and has leading brands in an attractive market. The core Jewellery segment is highly resilient and it is pretty difficult to see the business blowing up given the durability of the business model and strong balance sheet.

Valuation

My estimates have Richemont trading on a forward P/E ex cash of 20x and FCF yield of 4%. Note my earnings forecasts are well above consensus estimates given the operating leverage expected from higher sales per store. Consensus P/E ex cash is 23x. If we assume the multiple remains flat, the stock can return 12% (earnings growth) + 2% (yield) = 14% over the next few years.

Using a DCF across 10 years, with a discount rate of 10% and terminal growth rate of 4% delivers an IRR of 12.6%.

A combination of both valuation approaches gets us to a similar return of low-double digits. This is pretty good for a leading business with low double-digit earnings growth and strong financials. The company trades in-line with peers such as LVMH (21x fwd P/E), Kering (20x) and Moncler (24x) but is of higher quality with lower aspirational exposure, seasonality and more durable growth.

Summary

To wrap things up, lets summarise why Richemont is a high-quality, long-term compounder:

Leader in a highly attractive industry with long-term growth drivers

Superior product that is gaining share

Consolidated market with limited competition

Founder led with good management team

Latent pricing power to offset inflation

Scalable business model with inherent operating leverage

Strong balance sheet with net cash

Resilient business with customer and geographic diversification

Solid financials with good ROIC and margins

There is a pretty high degree of confidence the business will be bigger in 5 years time. It trades on a reasonable valuation. Looks good to me.