7 Powers - Why Starbucks does not have Scale Economies

Exploring Scale Economies in part 2 of 8 of 7 Powers Series

In the first part of the 7 Powers series, I described the key concepts behind Power and strategy that drives value.

I will now cover each Power. The first is Scale Economies, referred to by Helmer as:

A business in which per unit cost declines as production volume increases.

As a reminder, to have Power there must be an associated benefit and barrier.

Benefit: must be reflected in the cash flows through any combination of higher prices, reduced costs or lower investment needs.

Barrier: the benefit needs to persist - something that prevents rivals from copying or undercutting a company’s success. Without it, profits attract competition, leading to value-destroying arbitrage

For scale economies, the benefit is:

Reduced costs and a lower cost to serve than competitors.

A lot of companies have this benefit and can come from factors such as higher utilisation over fixed costs, density of customers per area, bulk purchasing discounts and learning economies.

The question is what prevents other players from competing this away. This is the Barrier known as:

Prohibitive costs of share gains

It needs to be uneconomical for a follower to break in and where the more rational decision would be to maintain inferior economics. In order to gain share, the follower would need to provide better value through lower prices or new products. The barrier is harder to attain than the benefit.

Helmer uses the example of Netflix and its strategy to invest in original content as a means of creating a barrier. Before this, the company was just a streaming business providing externally sourced content. Another company could bid for this same content over time and drive the costs higher.

By producing its own content, Netflix transitioned from a variable to fixed cost model with much higher upfront costs. The economics worked as costs were spread across its leading subscriber base. For smaller competitors developing a comparable level of content, per subscriber costs are higher and operating margins lower. The alternative is to invest less in content and see market share losses. This is often the more rational choice.

Helmer explains the dynamic as:

Surplus Leader Margin (SLM) - the profit margin the business with Power can expect to achieve if pricing is such that its competitors profits are zero

The formula is:

Surplus Leader Margin = [Costs/ Leader Sales] * [(Leader Sales)/(Follower Sales)-1]

Simplified into:

Surplus Leader Margin = [Scale Economy Intensity] * [Scale Advantage]

What does this mean?

The SLM tries to break out the profit margins for the business with Power if the follower earns zero profits. The two parts are:

Scale Economy Intensity - the cost margin of the leader. The higher the better. Why? Potential disruptors would need to invest significantly to compete. If this is low, then the cost barriers are not that high.

Scale Advantage - the proportional sales advantage the leader has. The higher the better. Why? If the leader and follower sales are comparable then the scale advantage is close to zero, leading to no SLM.

If Netflix was still just a streaming business, the company would have no Power as the Scale Economy Intensity would be low.

I will now explore a practical example in my portfolio (Amazon) and another which I believe has the benefit of scale economies but no Power (Starbucks).

Amazon - the Power of Scale Economies

The classic example of Scale Economies is Amazon across both AWS and Ecommerce. In this instance, I will just explore Ecommerce.

The value proposition is simple; fast delivery, low prices and broad selection. No other competitor provides anything close in its main markets.

The benefit is a lower cost to serve than peers. Amazon’s cost to serve is difficult to break out given its highly complex business with multiple segments.

Amazon would have the lowest cost per delivery given its scale, know how and tech led operations. This enables the company to reinvest back into price, speed and selection to bring more value.

Qualitative commentary implies cost to serve continues to decline with Jassy noting:

Overall, we've reduced our global cost to serve on a per unit basis for the second year in a row, while at the same time increasing speed, improving safety and adding selection.

and

As we lower our cost to serve, we can add more low ASP selection than we can support economically which coupled with our fast delivery puts Amazon in a consideration set for increasingly more shopping needs for customers.

What is the barrier?

In the world of retail, consumer preferences shift quickly and many past giants have faded. What is the barrier that stops other players from doing the same to Amazon?

It’s the infrastructure and Prime benefits.

To offer something comparable, a new player would need to invest >$200b in infrastructure and develop an efficient and scaled platform. The follower would also need to introduce a membership model with free same day shipping, loads of movie and TV content and more.

These are all significant fixed cost investments that are highly prohibitive for competitors. Amazon can make it work given scale with >5x GMV (gross merchandise value) than its nearest competitor Walmart and >40% US market share. The company has >200m Prime members globally and can spread the significant Prime costs across this large subscriber base.

To make matters worse for competitors, Amazon earns low retail margins (retail profits/GMV) of 2-3%. Traditional retailers who despite having higher expenses associated with running stores earn retail margins closer to 3-5%. Amazon has strategically reinvested in delivering a stronger value proposition, reducing margins and increasing barriers.

Power exists and it is best exemplified by the fact that in the highly competitive retail space, Amazon remains the clear leader with limited competitive threats in Ecommerce. No one has a solution that comes close. Peers don’t have the same scale. It makes no economical sense to make these large fixed cost investments to go on and deliver at low-single digit margins.

Can Temu be a challenger?

The only player that is proving a notable threat is Temu, owned by Pinduoduo. Temu has been able to gain a foothold in Amazon’s markets as it ships goods direct from manufacturers in China with prices sometimes 80% lower than Amazon. Around 60% of Amazon’s top China sellers are on Temu.

Temu has attracted a portion of Amazon’s customer base; the value conscious consumer. Global GMV has increased from $18b in 2023 to $51b in 2024 - quite remarkable. This has been underpinned by super low prices and aggressive marketing. Temu has yet to reach profitability and has negative unit economics.

New business models can come up that supersede Power.

This is ultimately where strategy comes into play. Amazon has consistently fended off competition with a strategy of returning scale economies back to customers and driving a better value proposition.

In this case, the company launched its own low cost platform for items under $20 called Haul across developed markets. Prices are competitive but slightly higher than Temu. Haul has the advantage of an efficient localised returns process, a strong brand and a trustworthy screening process that protects shoppers from lower quality goods.

While seller fees are being reduced in some categories to ensure selection is broad and prices are kept low. These strategic moves are designed to put pressure on competitor economics and growth.

In the recent quarter, PDD’s non-GAAP operating profit margin dropped from 33% to 19% - a significant decline. PDD does not disclose Temu’s economics and remains coy on releasing information. In its call, management noted at a group level:

While we view these expenses as long-term investments, there remain the mismatch between the returns and business investment cycles. Therefore, our profitability is likely to face challenges in the near-term and potentially over a longer period.

Temu has cut marketing spend and raised prices in the US. The result being a significant drop in sales.

Along with the elimination of tax loopholes, Temu faces an uphill battle to reach profitability. Time will tell.

Amazon has the advantage of both Power and strategy to keep them ahead and are increasingly making it uneconomical for new threats to profitably gain share.

Starbucks, a scaled leader with no Power

It is ironic that I am sitting in a Starbucks cafe right now writing this (talk about channel checks!). The spot is nice and cosy and serves a pretty good matcha frappuccino. Starbucks has delivered exceptional growth and returns for shareholders.

The company has scale with 40k stores in 80 countries and 16k in the US alone. It has the benefit of:

37% US market share that drives lower unit costs and efficiencies

Supplier purchasing power when buying raw materials

Learning curve advantage through extensive training programs

Store density improving distribution costs

The benefit of Scale Economies is there.

Is there Power?

For there to be Power there needs to be a barrier.

In this case, what is stopping independent coffee stores or even large chains from scaling. The economics work for new entrants.

To set up a coffee chain, you invest in fixed costs such as equipment, store fitout and people. The cost barriers are not high and thus Scale Economy Intensity is low.

Further, Starbucks’ lower cost to serve does not translate into lower prices or innovative products. Rather, it is returned via a nice ambience and store layout which does not prevent new entrants.

Chinese coffee chains have even been able to offer high-quality coffee at more affordable prices. Luckin in China has better unit economics despite lower prices.

Competitive intensity has increased globally. In the US, players such as Dunkin Brands (9.1k stores), Dutch Bros (900) and now Luckin Coffee are growing stores. Starbucks is also facing intense competition in China. The frequency of new entrants is a good indication of the lack of a barrier.

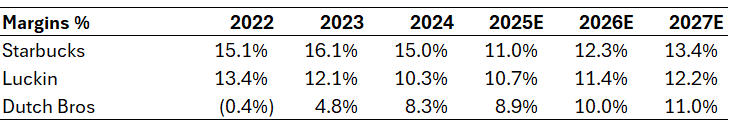

The result has seen previous high returns diminish and margins fall. As seen below, Starbucks’ margins are now closer to peer levels. The market has this going back up but I am sceptical.

Scale does not impede new players from growing. Competitors can lower prices or provide higher value products and still remain profitable. Starbucks lacks Scale Economy Intensity and therefore has no Power.

How could it have gained Power?

From my perspective, although Starbucks invested in a vertically integrated supply chain and lowered its cost to serve, these benefits were not returned via tangible value such as lower prices or higher quality products. Rather the value seems to lie in the experience is not a prohibitive barrier to followers.

The loyalty program could also be expanded into a membership platform like Amazon with a range of benefits to drive broader rewards and more stickiness.

Is it a declining business? Time will tell. Maybe it has Brand Power.

Competition is rising and switching costs are fairly low. The company can still do well by turning around operations or for industry growth to accelerate.

The point is that without Power, companies can often do well for a reasonable period of time. But persistent differential returns are hard to achieve as competition will invariably erode returns.

Disclaimer: All posts on “cosmiccapital” are for informational purposes only. This is NOT a recommendation to buy or sell securities discussed. Please do your own work before investing your money.